A Card from Your Aunt

Open it. Maybe there's money.

Hey, you got a card from your aunt.

Look at that. Where does she find these things.

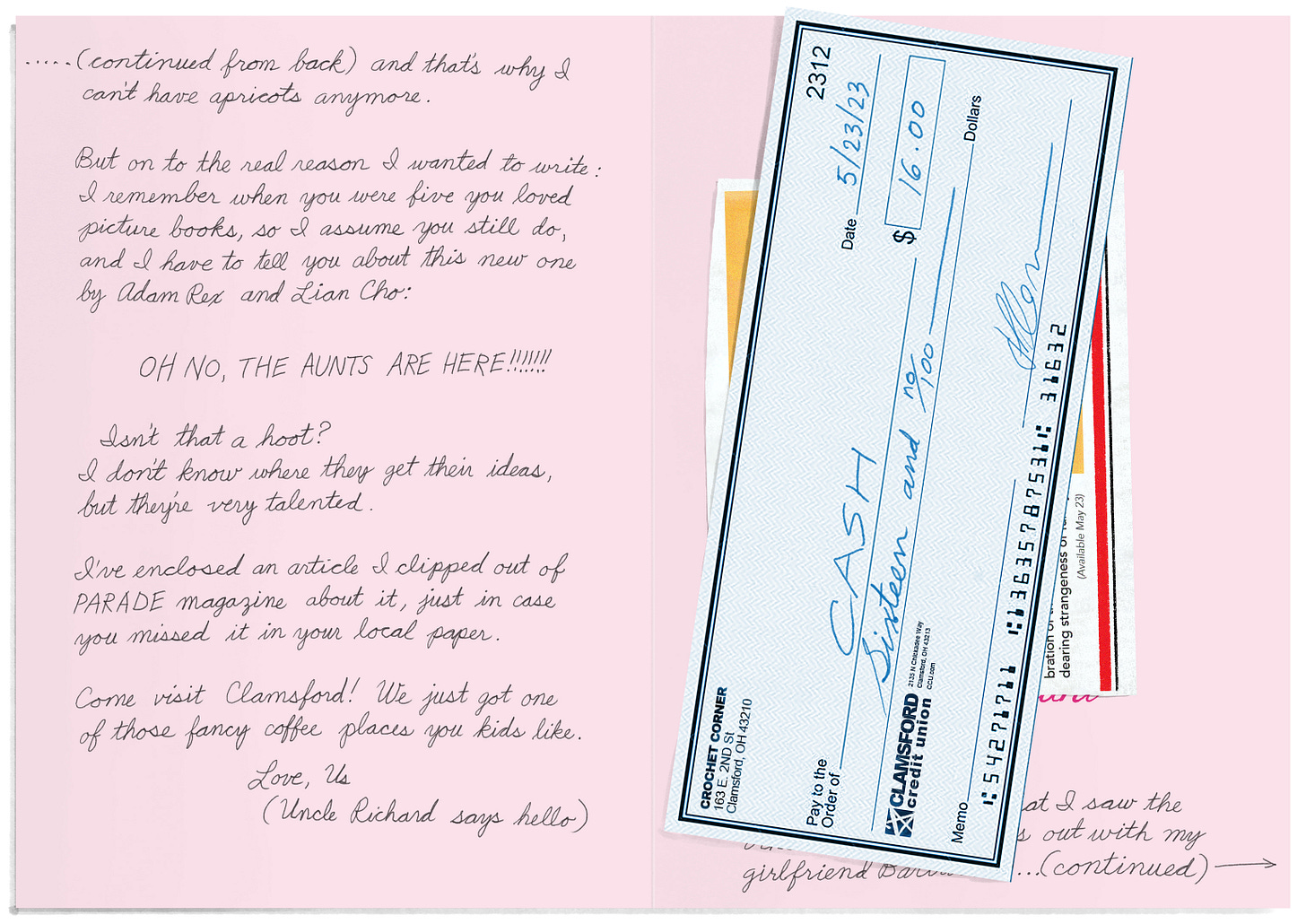

Oh, sweet—a check for sixteen dollars.

Look, she drew her own quotes around “Love.” What’s that supposed to mean.

Wait—what’s this about a magazine clipping?

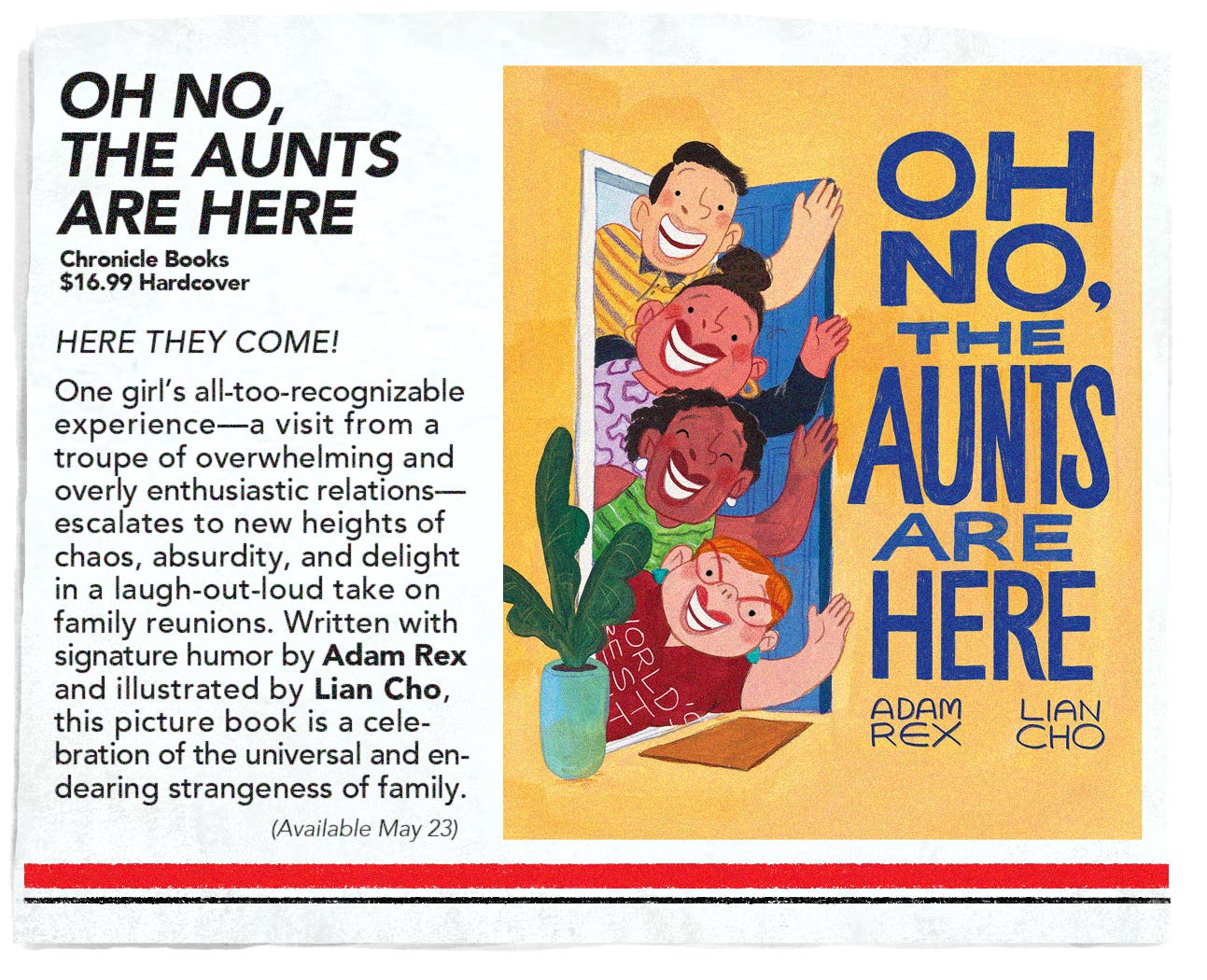

Aha, here it is.

Aw, that’s nice! Your aunt sent you a clipping about my new book with Lian Cho, OH NO, THE AUNTS ARE HERE. It comes out in a month!

It’s all about that sometimes great but always overwhelming feeling when you’re a kid and a bunch of relatives come to visit. I’ll talk next month about where it came from, but for now I’m just going to say that it can be preordered from your favorite bookseller, and preorders make a big difference. How about Antigone Books in Tucson?

Anyway, I love this book. I hope it’s a success.

What makes a book a success, you might be wondering. Is it a success if it touches just one human heart?

Well…yes. But in a more accurate sense, no. If I work for six months on the same book and touch one heart, then that’s a very low heart/time ratio. So one way I think about the success of a book is whether it earns out.

Earns Out?

Please stop shouting, but yes. Traditional publishers pay creators of a book an advance against royalties. Along with the printing budget (how big of an initial print run? How many bells and whistles?) and the marketing budget (and probably some other stuff I don’t know about), the advance gives some indication of the publisher’s expectations for the book. My advance is the only part I can really know with any specificity.

The typical royalty is 10% of the cover price, split evenly in picture books if the author and illustrator are separate people. I never have to pay back my advance—it’s mine—but if a book doesn’t sell enough to cross that tipping-point number where the cumulative royalty exceeds the amount of advance already paid? Then I just never make any more money from that book. And that happens enough that I agree to work with publishers assuming that the advance is all I’ll ever earn. I don’t ever cross my fingers and count on future dividends.

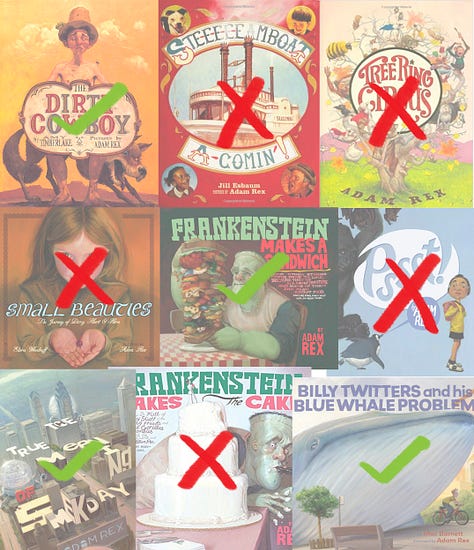

Anyway—if a book does cross that tipping-point threshold, then it’s said to have earned out. Let’s look at my first nine books.

Hey—my first ever picture book, The Dirty Cowboy written by Amy Timberlake, earned out! Success? I don’t know. A lot of that has to do with having been paid a very low advance. And I was essentially paid the same advance for my second book, which has had 18 years to earn out and hasn’t. My 3rd and 4th are now out of print, my 5th was a solid success, my 6th wasn’t, my debut novel has done pretty well but that’s what a movie adaptation will get you, I don’t think my 8th earned out, but I do think my 9th did. Maybe only because the author mentioned it in a Ted Talk, but still.

That’s more Xs than checks! So you’re asking: are those red-X books failures?

Not if they touched just one human heart. How dare you.

Once again, here are the last three files I opened in Photoshop, presented without context:

I'm always happy for a chance to tell you that PSSST! touched the human heart that is my kid Ramona's, in that it was her favorite favorite for so many years.

I recently had a fairly demoralizing experience where a book I had previously earned out on was suddenly MASSIVELY (tens of thousands of dollars) in the hole on royalty statements, and I was like, "wait, did EVERYONE return their copy?" Turns out they never applied my advance in the early years of the book's existence, so I thought I had earned out, but had not. Or maybe it did, who knows. But now I'm back to earning against the advance. I also see earning out as success -- maybe not the only success, but certainly a particular ladder rung of success, and I'm still wrapping my brain around what it means if I suddenly find out I'm a lot closer to the ground on that book than I thought I was. Also it just feels kinda mean, but the royalties man I talked to on the phone couldn't really speak to that.

Thanks Aunt Adam and Aunt Lian!